Welcome to the companion site for ARH 4450 and “Secret Societies of the Avant-garde.” Here you can find links to helpful sites as well as a forum for communicating with your classmates.

Source: Initiator4450

Welcome to the companion site for ARH 4450 and “Secret Societies of the Avant-garde.” Here you can find links to helpful sites as well as a forum for communicating with your classmates.

Source: Initiator4450

Filed under Uncategorized

This semester we will be playing Modernism vs. Traditionalism: Art in Paris, 1888-89 a Reacting to the Past game.

You can find the game book and supplemental readings posted on Sakai. You will receive your roles in class on March 27.

Video: Reacting to the Past: The Faculty Perspective

Video: Reacting to the Past: The Student Perspective

Schedule:

4/3 Introduce yourself in character with one image

4/8 Salon of 1888: Presentations and awards given by Academy members; Academic artists’ speeches

4/10 Debate future of art: Avant-garde artists’ speeches; Happy New Year!

4/15 Critics’ and dealers’ speeches; Critic Tickets presented

4/17 Plan for 1889 Exposition; The Academy must decide who to include; Dealers should solicit artists for their booths; Others should plan if they will do solo or group shows

4/22 Universal Exposition of 1889; Present and sell your work at the Exposition; Class will be held in Handwerker Gallery, which we will transform into the World’s Fair of 1889.

Photos from Spring 2014 re-staging of Paris Fair

Photos from Fall 2013 re-staging of Paris Fair

You should plan to post the written version of your speech on this page.

Links to supplementary materials:

Filed under Uncategorized

Part III highlights some of the art movements of the modern era. Below are links to the readings/videos.

Neoclassicism, Romanticism, and Realism

Fauvism and Cubism

Dada and Surrealism

Abstract Expressionism

Cool article on restoration/rehab of Pollock

Pop!

Filed under Uncategorized

Part II looks at the visual culture created in Western Europe from ca. 1400 to 1789.

Your essay question for Exam 2 will be chosen from the following list. Remember to cite and describe visual examples in your answer. You should use the major monuments as evidence in your answer, paying close attention to how they convey meaning and support your argument. You should also make sure to make reference to at least three artists and three objects in your answer.

The Renaissance in Florence: Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael

The Renaissance in Venice: Giorgione and Titian

Baroque Drama: Bernini, Velazquez, Caravaggio, and Gentileschi

The 17th c. in the North: Rubens and Rembrandt

The Rococo: Watteau, Boucher, Fragonard

Filed under Uncategorized

Part I looks at visual culture of the Western World created in Greece, Rome, and Europe between 500 BC and 1400 AD.

Links to the readings for the first section of the course can be found below.

Your essay question for Exam 1 will be chosen from the following list. Remember to use visual exams and make reference to the readings in your answer. Your essay should be legible; be free of grammatical and spelling errors; have an introduction and a conclusion; and make reference to at least three objects.

The Ancient World: Focus on Greece

The Ancient World: Focus on Rome

The Medieval World: Monasteries and Manuscripts

The Medieval World: Gothic Cathedrals

A few notes on Christianity

Christianity developed out of Judaism in the 1st century C.E. It is founded on the life, teachings, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, and those who follow him are called Christians. Episodes from the life of Jesus as recounted in the Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) form the principal subject matter of Christian visual art.

These include the: Annunciation, Incarnation, Visitation, Nativity, Adoration of the Shepherds, Adoration of the Magi, Presentation in the Temple, Massacre of the Innocents, Flight into Egypt, Baptism, Marriage at Cana, Miracles of Healing, Calling of Matthew, Raising of Lazarus, Transfiguration, Tribute Money, Last Supper, Agony in the Garden, Betrayal, Crucifixion, Deposition, Lamentation, Resurrection, Noli Me Tangere, and Ascension.

Filed under Uncategorized

This semester you will write a response to an object selected from the permanent collection at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum on the campus of Cornell University.

What to take with you: Take a notebook and a pencil, so you can take notes or sketch the work. Most museums do not allow pens, so do not take one.

Museum and gallery Do’s and Don’ts: Be courteous to other visitors. Never touch a work of art. Do not take photos unless you are sure this is allowed. If in doubt, ask.

When you find an artwork you would like to write about, stop and consider what it is that drew you to it. Then write a careful description of what you see. You can use the museum’s label and research to help you understand the artwork more fully, but the primary focus of this assignment is what you SEE, so take ample time to look at the work in detail. Consider the following formal elements, design principles, and media/techniques when composing your response.

Formal Elements

Line: Do you see any outlines that define objects, shapes, or forms? Are lines used to emphasize a direction (vertical, horizontal, diagonal)? Describe the important lines: are they straight or curved, short or long, thick or thin? How do you think the artist utilized line to focus attention on certain objects, forms, or people? Are any invisible lines implied? For example, is a hand pointing, is the path of a figure’s gaze creating a psychological line, or is linear perspective used? Do the lines themselves have an expressive quality?

Light: If the work is a two-dimensional object, is a source of light depicted or implied? Is the light source natural or artificial? Do the shadows created by the light appear true to life, or has the artist distorted them? In what way does he or she depict such shadows—through line, or color? If the object shown is three-dimensional, how does it interact with the light in its setting? How do gradations of shadows and highlights create form or depth, emphasis or order in the composition?

Color: Which colors are used? If the object is black and white, or shades of gray, did the artist choose to do this because of the media he or she was working in, or do such shades create a certain mood or effect? Color can best be described by its hue, tone, and intensity (the hue is its basic shade, for example blue or red). Does the artist’s choice of color create a certain mood? Does he or she make use of complementary colors—red/green, violet/yellow, blue/orange—or analogous ones (those next to each other on the color wheel)? Does the artist utilize colors that are “warm” or “cool”? In which parts of the work? Is atmospheric perspective—in which cool colors recede, creating a blurred background, and warm, clear colors fill the foreground—used?

Texture: What is the actual texture on the surface of the object? Is it rough or smooth? What is the implied texture? Are patterns created through the use of texture? Can you see brushstrokes or is the surface smooth?

Shape: What shapes do you see? If the work has a flat surface, are the shapes shown on it two-dimensional, or are they made to appear three-dimensional or volumetric? If the work is a three-dimensional object, how volumetric is its shape? Is it nearly flat, or does it have substantial mass? Is the shape organic (seemingly from nature) or geometric? In representations of people, how does shape lend character to a figure? Are these figures proud or timid, strong or weak, beautiful or grotesque?

Space: How does the form created by shape and line fill the space of the composition? Is there negative, or empty, space without objects in it? If the artwork is three-dimensional, how does it fill our space? Is it our size, or does it dwarf us? If the piece is two-dimensional, is the space flat, or does it visually project into ours? How does the artist create depth in the image (by means of layering figures/objects, linear perspective, atmospheric perspective, foreshortening of figures)?

Design Principles

Emphasis: The emphasis of a work refers to the object’s focal point. What is your eye drawn to? Does the artist create tension or intrigue by creating more than one area of interest? Or is the work of art afocal or all-over ― that is, there is not a particular place to rest the eye?

Scale and Proportion: What is the size of all the forms and how do they relate proportionally to one another? Did the artist create objects larger in scale in order to emphasize them? Or was scale used to create depth? Are objects located in the foreground, middle ground, or background? Look at the scale of the artwork itself. Is it larger or smaller than you expected?

Balance: Balance is produced by the visual weight of shapes and forms within a composition. Balance can be symmetrical—in which each side of an artwork is the same—or asymmetrical. Radial balance is when the elements appear to radiate from a central point. How are opposites—light/shadow, straight/curved lines, or complementary colors—used?

Rhythm: Rhythm is created by repetition. What repeated elements do you see? Does the repetition create a subtle pattern, a decorative ornamentation? Or does it create an intensity, a tension? Does the rhythm unify the work, or does it, on the contrary, seem a group of disparate parts?

Unity/Variety: Is the artwork unified or cohesive? How does the artist use the elements to achieve this? Or is there diversity in the use of elements that creates variety? How does the artwork combine aspects of unity and variety?

Media and Technique

Is the object two- or three-dimensional? What limitations, if any, might the chosen medium create for the artist?

Painting: How did the type of paint affect the strokes the artist could make? Was it fresco, oil, tempera, or watercolor? Was it a fast-drying paint that allowed little time to make changes? What kind of textures and lines was the artist able to create with this medium? Does it lend a shiny or flat look? How durable was the medium? Does the work look the same today as when the artist painted it?

Drawing: Consider the materials utilized: metal point, chalk, charcoal, graphite, crayon, pastel, ink, and wash. Is the artist able to make controlled strokes with this medium? Would the tool create a thick or thin, defined or blurred line? Was the drawing intended to be a work of art in itself, or is it a study for another work, a peek into the artist’s creative process?

Printmaking: What is the process the artist undertook to create this work? Did he or she need to carve or etch? Did the medium require a steady hand? Strength, or patience?

Sculpture: Is the sculpture high or low relief, or can we see it in the round? What challenges did the material present to the artist? Was the work created through a subtractive process (beginning with a large mass of the medium and taking away from it to create form), or an additive one? What tools did the artist use to create the form? If the form is human, is it life-size?

1. Identify the artist’s decisions and choices.

1. Identify the artist’s decisions and choices.

Begin by recognizing that, in making works of art, artists inevitably make certain decisions and choices- What color should I make this area? Should my line be wide or narrow? straight or curved? Will I look up at my subject or down on it? Will I depict it realistically or not? What medium should I use to make this object? And so on. Identify these choices. Then ask yourself why these choices were made. Remember, although most artists work somewhat intuitively, every artist has the opportunity to revise or redo each work, each gesture. You can be sure that what you are seeing in a wok of art is an intentional effect.

2. Ask questions. Be curious.

Asking yourself why the artist made certain choices is just the first step. You need to consider the work’s title: What does it tell you about the piece? Is there any written material accompanying the work? Is the work informed by the context in which you encounter it-by other works around it, or, in the case of sculpture or architecture, by its location? Is there anything about the artist that is helpful?

3.Describe the object.

By carefully describing the object, both its subject matter and how its subject matter is formally realized, you can discover much about the artist’s intentions. Play careful attention to how one part of the work relates to the others.

4. Question your assumptions.

Question, particularly, any initial dislike you might have for a given work of art. Remember that if you are seeing the work in a book, museum or gallery, someone likes it. Ask yourself why. Often you will talk yourlself into liking it, too. But also examine the work itself to see if it contains any biases or prejudices. It matters, for instance, in Renaissance church architecture, whether the church is designed for Protestants or Catholics.

5.Avoid an emotional response.

Art objects are supposed to stir up your feelings, but your emotions can sometimes get in the way of clear thinking. Analyze your own emotions. Datermine what about the work sets it off, and ask yourself if this wasn’t the artist’s very intention.

6.Don’t oversimplify or misrepresent the art object.

Art objects are complex by nature. To think critically about an art object is to look beyond the obvious. Thinking critically about the work of art always involves walking the line between the work’s susceptibility to interpretation and its integrity, or its resistance to arbitrary and capricious readings. Be sure your reading of a work of art is complete enough (that it recognizes the full range of possible meanings the work might possess), and, at the same time, doesn’t violate or misrepresent the work.

7. Tolerate uncertainty.

Remember that the critical process is an exercise in discovery, that it is designed to uncover possibilities, not necessarily truths. Critical thinking is a process of questioning; asking good questions is sometimes more important than arriving at “right” answers. There may, in fact, be no “right” answers.

Filed under Uncategorized

What is art, where is it found, who makes it? The answers to these questions can range from Egyptian tomb paintings, to conceptual installations, to the Mona Lisa. Art is found in many places including houses of worship, tombs, forests, museums, galleries, post offices, flea markets, and department stores. And it can be made by anyone, anywhere.

Thomas Struth, Louvre III, 1989.

Struth is a German photographer. In this series he documented people interacting with (or in this case, perhaps not interacting with) art. In this case, three artistic mediums are at work: the paintings hanging on the wall, the architectural space (the Louvre, originally a 12th century palace, now one of the world’s largest museums), and the photograph.

Andy Goldsworthy, Forked sticks in water, High Bentham, Yorkshire, March 1979.

Goldsworthy is a British sculptor, photographer, and environmentalist who creates site-specific land art. This piece itself is ephemeral, it will fade with time, but the photograph documents its existence.

That we can recognize art in our everyday lives, and often find it all around us, raises the question of its value. Some art may be commonplace, other works extremely rare, but its worth can be counted in terms of religious, cultural, political, aesthetic, personal, or financial significance.

The power of art is evident from the many cases where its display has been censored. Visual communication is such a strong mode of expression that those with an opposing agenda may be worried that art will rouse viewers into action.

Diego Rivera, Man, Controller of the Universe, 1934 (Image courtesy of Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City).

A similar mural, Man at the Crossroads, was commissioned for the Rockefeller Center in New York, but was destroyed before it was completed because of the inclusion of a portrait of Lenin.

Richard Serra, Tilted Arc, 1981.

This 120-foot long Cor-ten steel structure by Richard Serra that was installed in Federal Plaza in lower Manhattan in 1981. It was removed in 1989 after much controversy, including public dislike. Amongst other things, it was accused of promoting vandalism, crime, and totalitarianism.

Of the work, Serra has said:

The viewer becomes aware of himself and of his movement through the plaza. As he moves, the sculpture changes. Contraction and expansion of the sculpture result from the viewer’s movement. Step by step the perception not only of the sculpture but of the entire environment changes.

What is Art History? Art History is a branch of historical inquiry that studies visual culture, specifically painting, sculpture, architecture, and the graphic and decorative arts. Art Historians evaluate and explain art as expressions of the philosophical, political, and religious concerns of the cultures that produced them and use visual culture to reconstruct the past and situate objects in history.

Art history begins with the object. The first thing art historians do is to engage in close looking and analysis of an object. This is called formal or visual analysis, and it is the beginning of an art historian’s journey with a work of art. Here are some things to think about when looking at an object:

Content: Does the work clearly depict objects or people as we would recognize them in the world around us (is it representational)? Alternatively, is its subject matter completely unrecognizable (is it non-objective)? To what degree has the artist simplified, emphasized, or distorted aspects of forms in the work (or abstracted it)? What effect does the way the subject is depicted have on its meaning?

Iconographic analysis: Are there things in the work that you can interpret as signs or symbols? For example, is there anything that suggests a religious meaning, or indicates the social status of somebody depicted in the work?

Biographical analysis: Would information about the life of the artist help you to interpret the work?

Contextual analysis: Would you understand the work better if you knew something about the history of the era in which it was created, or about religious, political, economic, and social issues that influenced its creation?

Feminist analysis: Is the role of women in the artwork important? Is the artist commenting on the experience of women in society? Is the artist a woman?

Let’s analyze the following painting, Landscape with Christ Appearing to Mary Magdalene (1681) by Claude Lorrain, using these modes.

Content and Iconography

The landscape is painted in a representational manner (it resembles nature) but it is also idyllic (it is calm, peaceful, and serene; this feeling is created by the emphasis on horizontal lines and the use of a harmonious color palette). This work is historiated or Classical because it contains signs (iconographical elements) that indicate a historical (Biblical or mythological) narrative. This particular story comes from the Gospel of St. John (20:11-18). On the far right on top of the hill (Golgotha) are three crosses. Below the crosses cut into the base of the hill is a tomb. An angel sits in the tomb’s open door. Standing next to the fence’s open gate are two women (Mary the Mother of James and Salome). Farther to the left is a man wearing a gardener’s hat and holding a spade (Jesus) and a woman kneeling (Mary Magdalene). In the lower left hand corner of the composition is a second angel. If you recognize the symbols and the figures you can identify the story as Easter Morning when Christ appears to Mary Magdalene and says to her “Noli me tangere” or “Touch me not, for I am not yet ascended to my Father.”

Biography

Claude was a seventeenth-century French landscape painter who trained and worked in Rome. This painting is from Claude’s late period and shows the elongation of figures and heightened mood scholars associate with his later works. He often included architectural ruins of Ancient Rome in his works. In the center of this painting is a city, meant to represent Jerusalem.

Contextual

This painting, and its pendant St. Philip Baptizing the Eunuch, was created between 1678 and 1681 for Cardinal Fabrizio Spada, who worked to convert Calvinists to Catholicism in Savoy. This painting reinforces his ecclesiastical mission, as it depicts the moment when Mary Magdalene witnesses Christ’s divinity, or becomes a believer. It is a Counter-Reformation painting that embodies the Tridentine Edicts that art be Biblically-based, legible, and emotive.

The Council of Trent, contrary to John Calvin’s reading of the Gospels, reaffirmed Gregory the Great’s composite view of Mary Magdalene as a reformed prostitute, making her the penultimate penitent sinner and saint. In contrast to the Protestant doctrine of grace, Mary Magdalene represented the sacrament of penance for 17th-c. Catholic viewers. She symbolized conversion, contemplation, and asceticism.

Feminist

Mary Magdalene is a compelling character for feminists and has, at times, been held up as a proto-feminist and significant heroine, although this may say as much about her interpretors as it does about her. Furthermore, feminist content would not have been the intention of Claude, or his patron, Cardinal Spada.

By using these various modes, combined with careful looking (formal/visual analysis) we can develop a better understanding of this painting and its historical significance.

Click below for more on Claude:

It is also valuable to look at other depictions of the same subject–especially those that may have been seen by the patron or artist and thus influenced their ideas for the composition. How does Claude’s composition differ from these notable precedents?

Fra Angelico, Noli me tangere, 1440-41; Fresco, Convent of San Marco, Florence

Titian, Noli me tangere, 1514; National Gallery, London.(http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org/titians-noli-me-tangere.html)

Let’s employ the modes of analysis previously discussed to help us understand this antique statue.

Augustus of Prima Porta, 1st century CE

Augustus of Prima Porta, 1st century CE

Description/Formal analysis

This monumental (larger-than-life-size at 6’8″) sculpture in white marble depicts a barefooted man (identified in the title as the Emperor Augustus) wearing a traditional Roman breast plate (called a cuirass, this was worn by members of the military) with the voluminous drapery of a Senator’s toga wrapped around his waist and left arm. His right arm is raised and he points with his right index finger. At his right foot is a small winged child riding a dolphin. There are scenes depicted in relief on his cuirass.

Context

The Augustus of Prima Porta was commissioned in 5 CE by Augustus’ adopted son Tiberius. At the time it was made Augustus was almost 70 years old, but he is depicted as a young man in his prime. It was discovered at Prima Porta, the villa belonging to Augustus’ wife Livia, located nine miles outside of Rome. This statue and its decorative program were used by Tiberius as a form of propaganda so that the viewer would recall the important role Augustus played in securing the Roman empire and ushering in the era of Roman Peace (Pax Romana).

Style and Iconography

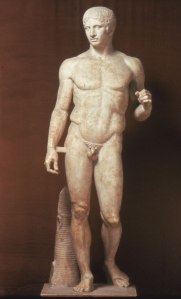

Augustus is portrayed as a victorious general (the cuirass) making a speech (gesture and toga=Senator), but he is posed similarly to the Classical Greek sculpture known as the Doryphoros. The Doryphoros (shown below) demonstrates Polykleitos’s canon of perfect proportions and represents the ideal human form, a nude, male athlete.

Polykleitos, Doryphoros, ca. 450-40 B.C., from Pompeii, Naples, Museo Archaeologico.

Polykleitos, Doryphoros, ca. 450-40 B.C., from Pompeii, Naples, Museo Archaeologico.

The Augustus Prima Porta combines the idealized features of strength and beauty found in the Doryphoros, with the personal features of Augustus: a broad forehead, deep-set eyes, a well-formed mouth, and a small chin. The clear Greek inspiration in style and symbol is a central part of the Augustian ideological campaign and a clear shift from the Roman Republican-era iconography where old and wise features were seen as symbols of solemn character. The Primaporta statue marks a conscious reversal of iconography back to the Greek classical and Hellenistic periods in which youth and strength were valued as signs of leadership.

Augustus is portrayed as a perfect leader with flawless features, personifying the power and authority of the emperor who had the capacity to stabilize a society and an empire. This is emphasized through the iconography of the breast plate that shows Augustus brokering a peace with the Parthians who return the royal standard to the Romans. This scene is surrounded by images of the gods.

Scholars debate the identification of all the gods but one interpretation is as follows: at the top is Caelus, the sky god. Below him are the Sun god, Sol in a four horse chariot and Aurora riding a female figure. On the left is a figure of Hispania and at the right a captive female barbarian. Apollo and his lyre on a winged griffin and Diana on the back of a stag that crowned the Arch of Gaius Octavius on the Palatine come beneath. Below, the Mother Earth Tellus reclines and cradles two babies and a cornucopia full of fruits. Both the images of the sky god and the Mother Earth imply peace that results from the victory. The gods on the breastplate suggests that Augustus’ victory has a cosmic favor. (http://web.mit.edu/21h.402/www/primaporta/description/breastplate/)

Scholars debate the identification of all the gods but one interpretation is as follows: at the top is Caelus, the sky god. Below him are the Sun god, Sol in a four horse chariot and Aurora riding a female figure. On the left is a figure of Hispania and at the right a captive female barbarian. Apollo and his lyre on a winged griffin and Diana on the back of a stag that crowned the Arch of Gaius Octavius on the Palatine come beneath. Below, the Mother Earth Tellus reclines and cradles two babies and a cornucopia full of fruits. Both the images of the sky god and the Mother Earth imply peace that results from the victory. The gods on the breastplate suggests that Augustus’ victory has a cosmic favor. (http://web.mit.edu/21h.402/www/primaporta/description/breastplate/)

Augustus’s barefeet and the inclusion of Cupid riding a dolphin as structural support reveals Augustus’s supposed mythical ancestry. Cupid is the son of the goddess Venus who was the ancestor of Augustus’s adopted father Julius Caesar.

In sum, this statue is a propagandistic portrait of the emperor that depicts him as a charismatic orator, heroic military leader, just statesman, and divine ruler who has ushered in a period of growth, peace, and stability for the Romans.

For more on the Augustus of Prima Porta see:

Augustus of Primaporta – Smarthistory.

For more on Roman history see:

Filed under Uncategorized

The Department of Art History strongly seeks to promote shared cultural and intellectual engagement outside of the classroom. Therefore, students enrolled in an art history course are required to attend 2 departmental or visually based events during this semester and write a response to each.

One of these events must be sponsored by Handwerker Gallery

The other event can be sponsored by the Handwerker or it can be something in the community. Some ideas:

First Friday Gallery Night

Downtown galleries and art houses of Ithaca host exciting First Friday monthly evening receptions for their latest art exhibits, showcasing the work of local, national, and international artists. Gallery Night is free and open to the public and takes place on the first friday of each month from 5-8 pm at participating downtown Ithaca galleries. Gallery guides with a map of participating locations and show descriptions are available at all participating galleries at Gallery Night.

free public tour

3 p.m., last Saturday of each month

Lisa Sanditz, Earthships and Their Neighbors, 52″ x 66″, 2005 courtesy of artist’s website

This blog accompanies ARTH 11100 Episodes in Art History. The chosen topics, primarily based on painting and sculpture from the western tradition, will be discussed from a variety of perspectives, including style, artists’ techniques and materials, potential meanings, and historical context.

formerly What Sorts of People

Peer-populated resources for art history teachers

companion site to Episodes in Western Art

Tamed Cynic

companion site to Episodes in Western Art

This was originally a blog for information for students traveling to Italy - it has evolved to a general blog about traveling to Italy and beyond!

companion site to Episodes in Western Art

National Emerging Museum Professionals Network

companion site to Episodes in Western Art

companion site to Episodes in Western Art

companion site to Episodes in Western Art

companion site to Episodes in Western Art

companion site to Episodes in Western Art

companion site to Episodes in Western Art

companion site to Episodes in Western Art

Just another WordPress.com site